Luís Vaz de Camões (1524/5 – 1579 or 1580), known as the “prince of poets,” is widely regarded as the greatest poet of Portugal and of all literature created in the Portuguese language. His skills are often compared to Shakespeare, Homer, Virgil or Dante. He left behind many lyrical works and dramas, the best known of which is Portugal’s national epic Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), or “sons of Luz,” after the name of the mythical forefather of the Lusitanians. Its influence on literary Portuguese is so great that it is often referred to as Camões’ language. The writer was also, according to the testimonies of his contemporaries, a good soldier, although he easily grabbed weapons and got into brawls. He displayed courage and bravery, and was always loyal to the king and honorable. He fell in love more than once. In one sonnet he wrote that “in various flames he variously boiled” (em várias flamas variamente ardia), but whether he had his muse and who she was remains a mystery.

The formation of Luis de Camões’ character as an artist was accomplished both through his classical education (Horace, Petrarch) and experiences at the royal court, and through the hardships of life as a sailor and soldier in India and Portuguese Africa. Going beyond the circle of courtiers freed him from the conventions of short works, while sailing and distant countries gave him a unique experience of loneliness and fear for his fate. The fruit was a saudade-soledade tone – longing and loneliness – previously unknown in Portuguese poetry. Hence his best works, such as elegies and canções, express real suffering along with sincerity of feeling and emotion. The cheerful and carefree face of Camões can be seen in redondilhas – light court compositions that give the impression of spontaneity and simplicity, with their subtle irony and humorous stanzas.

Posąg Camõesa na placu jego imienia w Lizbonie

Rhymes, Lusiadas and Apocrypha

The first edition of Camões’ Rimas was published fifteen years after his death. It was prepared by Fernão Rodrigues Lobo Soropita after painstakingly collecting works from manuscripts and copies. Nevertheless, the inclusion of works erroneously attributed to the Poet could not be avoided. The fame of the national epic grew in the 17th century to such an extent that it overshadowed the remaining poetic output of the Luzjad author. However, this did not stop the search for “undiscovered” poems, sometimes too easily attributing authorship to the author of Rimas. The poetic output of de Camões, however, was so rich and poorly known that even in the 19th century Visconde de Juromenha managed to add to his edition of l.1860-1869 many poems from songbooks that were known only to a narrow circle of scholars and experts. Suffice it to say that the number of sonnets in the editio prima was 65, while Juromenha published as many as 352. The number of poetry in toto, encompassing genres as diverse as odes, eclogues and elegies, for example, as well as poems of Portuguese origin (canções, redondilhas, motos, esparsas, glosas) rose from 170 in the 1595 edition to 593 in the l.1860 edition. 1860. Research conducted at the turn of the 20th century by Wilhelm Storck and Carolina Michaelis de Vasconcelos pointed out many poems mistakenly attributed to Camões. Work on the purification of the texts continues to this day.

I have experienced everything – and I am still burned by widowed grief over things lost

The Luzjadas consist of ten songs written in 10-note octaves (oitava rima), in which the Poet included, among other things, elaborate comparisons and onomatopoeias, and with the help of intensifying and weakening vowels, gained musicality in verse. The lusiads tell the story of Vasco da Gama’s expedition to discover a new sea route to India, thus being a praise of the “dangerous life” (vida perigosa) – for the good and glory of the homeland, and at the same time a warning for the Catholic rulers to unite against the expansion of Islam in southeastern Europe (the Battle of Mohacz was fought when the Poet was about a year old).

Camoes Square in Lagos

The epic begins with a prologue, an invocation addressed to the nymphs reminiscent of Virgil’s arma virumque cano, and a dedication to King Sebastian I. Also addressed to the ruler is the work’s concluding call for the reconquest – the recapture of Morocco: Do me a favor, and when you undertake matters/ Worthy of your Might, Power and Fame … When Atlas has fetched from the top as you have done to my Lord/ The power of Morocco and the power of the Turidan will be restored. (translated by Idziego Przybylski).

The poet develops the action of the work on two planes: mythological and historical, The first, referring to Homer and Virgil, is the terrain of the Olympian gods. The author introduces them for a reason – the discoveries, military superiority and bravery of the Portuguese surpass the heroic deeds and hardships of Aeneas, Achilles and Odysseus. The Olympians themselves are idolized outstanding people, which also opens the way for the Poet’s brave compatriots to apotheosis, which does not contradict the Christian wonderment present in the epic.

The historical plan covers origo gentis, the glorious history and achievements of the Lusitanians – conquerors, explorers and defenders of the Cross against the Mohammedans. Here we have past history, such as the assassination of Inês de Castro in 1355 or Vasco da Gama’s expedition, and new matters, such as the consolidation of Portugal’s position (and therefore the Catholic faith) in India.

Both plans are linked by the prophecy of Venus, foretelling the future glory and power of the Poet’s homeland, defeating not only evil men but also forces of nature, in the epic used by ancient deities hostile to the Writer’s homeland, with Bacchus at the head.

Outline of the Poet’s Profile

Childhood, schools and reading

The information available to us about the Maker’s life is not very abundant, a lot of anecdotes and a kind of folklore formed over the years around famous and charismatic people. The author’s collection of poetry entitled Parnas Luís de Camões (Parnaso de Luís de Camões) was lost while he was still alive. The poet came from a noble family, born as the only child of Simão Vaz de Camões and Ana de Sá de Macedo. There is some dispute about the place of his birth. We know that he died in the capital, Lisbon, while he was educated in Coimbra. Both cities claim to be the place of his birth. Based on the text of Luisiadas, Alenquer (my green and dear motherland – Alenquer) also appears among the possible localities. From Alenquer came his mother, related in the process to the well-known Portuguese humanist Damião de Gois, also from this city. The Camões family originated in Iberian Galicia, from where they moved to the north of the Portuguese kingdom, settling in the land of Chaves. When Luis was a boy, his father headed for India in search of fortune, dying in Goa a few years later. His mother remarried.

The poet studied with the Dominican and Jesuit fathers. For a while he attended the University of Coimbra, but the university’s documents contain no mention of him. The funds for his education were probably put up by Luis’ uncle, Bento de Camões. He was an influential man – the prior at the Santa Cruz Monastery, in addition to being the university’s chancellor.

Studying and reading the classics influenced Camões as a playwright, seeking to combine national traditions and classical models. In his comedy Amphitriones (Anfitriões (Enfatriões)), based on the work of Plautus, he emphasized the comic aspects of myth; in his comedy King Seleukos (El-rei Seleuco), he transformed the morally objectionable situation presented by Plutarch (Seleukos’ son binds himself to his stepmother) into pure farce. In Philodemos (Philodemo), he developed the native play, the auto morality play, popularized by Gil Vincente, putting it into classical laws, while increasing the role of the plot. Also on his comedies, he made the source of comedy mainly action rather than characters.

Periphery, war and prison

Biographers like to speak of Luis de Camões as a romantic and idealist. Playing at court as a lyric poet, he led, probably like William Shakespeare, a rather free life, entering into romances with courtesans, and probably also with women of “lower status.” He was said to have fallen in love with Catherine of Ataíde and Princess Maria, sister of King John III of Portugal. These feelings and probably an indiscreet allusion to that ruler in El-Rei Seleuco contributed to his exile from Lisbon in 1548.

The writer went to the land of Ribatejo in central Portugal, where he enjoyed the hospitality of friends for about six months. He enlisted in the army (perhaps due to some love disappointment) and in 1549 set off for Ceuta. While fighting the Moors of the Maghreb, he lost the sight in his right eye. He returned to the kingdom’s capital in 1551, but it seemed he was no longer the same man. He led a life in the likeness of bohemians and adventurers. In 1552, during a Corpus Christi procession in Largo do Rossio (today’s Pedro IV Square in Lisbon), he wounded Gonçalo Borges of the Royal Stables. He was captured and imprisoned, but thanks to the efforts of his mother, asking for mercy from royal ministers and the Borges family, he was released. Nonetheless, the Poet was fined 4,000 reals (réis) and required to serve three years in the colonial troops in India.

Overseas countries

So in 1553, he set out for the Portuguese Indies (Estado da Índia) aboard the São Bento, captained by Fernão Alves Cabral. They arrived at the shores of India after six months. Soon after setting foot ashore, Camões was again sent to a cell for a while, this time for debt. He called the city itself “the stepmother of all honest people.” He researched the local customs and had an excellent grasp of the geography and history of the surrounding land. During his first expedition, he joined a naval battle near Malabar, after which he took part in skirmishes on the routes of merchant ships between Egypt and India. The fleet, together with Camões, returned to Goa in November 1554. The poet did not forget his pen – on board he created as well as engaged in writing letters for “unlearned” sailors.

When his period of forced service – punishment for the wounding of Gonçalo Borges – came to an end, Camões was given an officer’s position (in English nomenclature chief warrant officer, a rank similar to ensign). He served in the recent 1557 founding of Macau, the first European city and trading port in China, by the Portuguese. Poet’s duties consisted primarily of managing the property of fallen and missing soldiers. In parallel, Camões worked on Os Lusiadas.

Unfortunately, there were accusations of embezzlement, and then the need to sail to Goa to defend himself before the royal tribunal there. During the return trip, near the mouth of the Mekong, his ship sank. It managed to save the manuscript, but the Poet’s Chinese lover, Dinamene, drowned. Legend has it that the Poet swam to shore holding the pages of his unfinished epic proudly above the water. A museum of him (Museu Luís de Camões) has been established in Macau, while a bronze statue of the Poet can be seen at the Archaeological Museum in Old Goa (Velha Goa). Until 1960, it was located in front of the building, in the garden, but was moved due to protests after Goa was incorporated into India. There is another statue of the Poet in the state capital of Goa – Panaji – it is a 12-meter-high pillar placed in the Jardim de Garcia da Orta Garden.

In Portugal

In 1570 he managed to return to Lisbon, where Os Lusíadas come out in print two years later. They are received as a testament to his great talent, and Camões becomes the most famous and respected poet of the Iberian Peninsula countries. He receives a small royal salary of 15,000 réis for his hardships in the service of the crown in India and China and, perhaps as a tribute to his epic.

In 1578, the Poet learns of the defeat at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in northern Morocco, also known as the “battle of the three kings.” King Sebastian I of Portugal and his ally, the deposed Sultan of Morocco Abu Adballah Mohammed II, were killed there. They were beaten by an army led by the new Sultan Abd Al-Malik I, backed by the High Porta. The heirless death of Sebastian I led to the end of the Aviz dynasty and the formation of a six-decade-long dynastic union with Habsburg Spain,

After the defeat, as Castilian troops approached Lisbon, Camões wrote to Captain General Lame: “soon everyone will see that my homeland was so dear to me that I was happy to die not only in it but with it.” The poet indeed ended his life two years later, aged 56, perhaps having contracted the plague. The day of his death – June 10 – according to the Julian calendar still in effect at the time (20 according to the Gregorian) is a Portuguese national holiday.

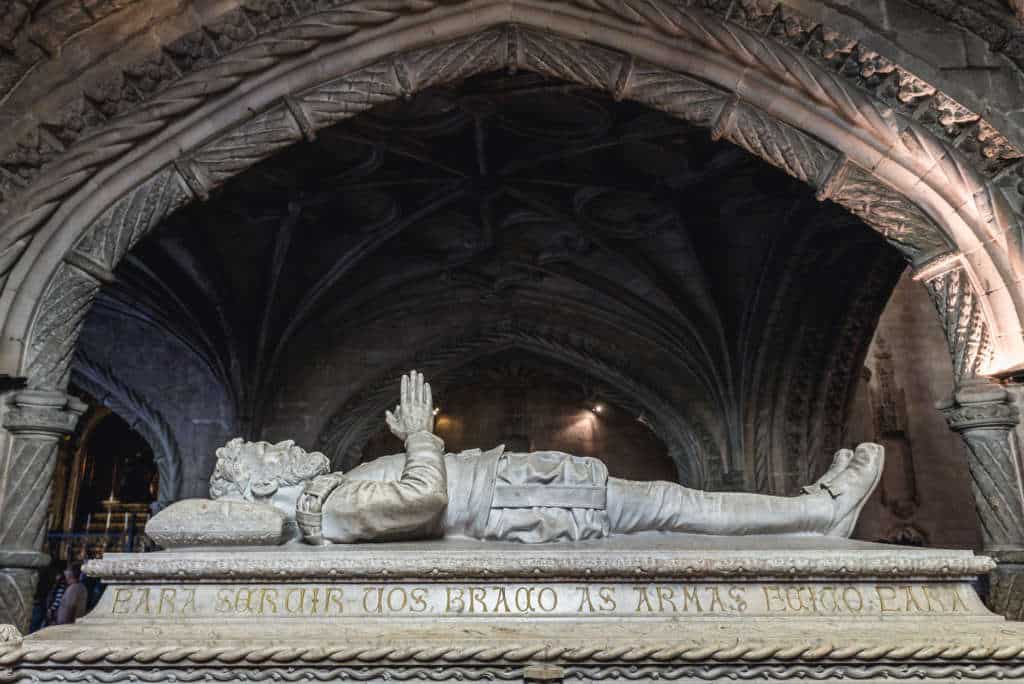

The tomb of Camoes at the Hieronymite monastery

After the defeat, as Castilian troops approached Lisbon, Camões wrote to Captain General Lame: “soon everyone will see that my homeland was so dear to me that I was happy to die not only in it but with it.” The poet indeed ended his life two years later, aged 56, perhaps having contracted the plague. The day of his death – June 10 – according to the Julian calendar still in effect at the time (20 according to the Gregorian) is a Portuguese national holiday.

The town of Constância has a monument and museum dedicated to the Poet, who was imprisoned there for a time. Luisa de Camões also depicts, among other things, the first Portuguese Romantic painting: Domingos Sequeira’s A Morte de Camões of 1825, now lost.

—–

Main photo, Camoes statue in Cascais

Sources:

Wikipedia article (Portuguese) https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lu%C3%ADs_de_Cam%C3%B5es#Vida,

Azevedo, Maria Antonieta Soares de. “Um Manuscrito Quinhentista de Os Lusíadas”. In: Colóquio de Letras, 1980,

Moisés, Massaud. A Literatura Portuguesa. Cultrix, 1997,

Pereira, Terezinha Maria Scher, “História e Linguagem em Os Lusíadas,

Encyclopaedia Britannica s.v. Luís de Camões https://www.britannica.com/print/article/91028